Each stitch is delicately sewn into the cloth, requiring patience and persistence. The stitches are all used to form a design that reflects the story and history of oneself.

Tatreez is a form of Palestinian embroidery that symbolizes existence, identity, resilience and is used to honor heritage. Tatreez is most commonly used on thobes (traditional Palestinian dresses), but are also on jackets, cushions, tablecloths, pillows, purses and more.

Lina Barkawi, founder of Lina’s Thobe, is a Palestinian Panamanian who went from having a blog of her own tatreez journey to teaching and inspiring others to tell their stories through this artform. Barkawi hosts virtual classes through her Tatreez 101 program. In the program there are 12 weeks of live office hour sessions, an active and supportive community and small accountability groups.

“I wish I had the resources, which is why I created my business,” Barkawi said. “I want to create that experience for someone where they have all the tools that they need to do it themselves because it is a super special experience.”

Tatreez became a symbol of resilience and displacement after the Palestine Nakba in 1948, where over 700,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes. As a result, women started to wear their thobes as a statement of the existence of their villages they had been expelled from. Thus, embroidery has been passed down from generation to generation to be preserved.

“There’s so much value because that ancestral practice is rooted in more than just consumption,” Barkawi said. “It’s rooted in your connection to other people, to your land, to your identity and that part is really quite priceless.”

Six years ago, Barkawi’s mother recommended they take a Palestinian embroidery class together, and that was when Barkawi realized the cross stitch she learned growing up was a form of tatreez.

“It’s not necessarily that the technique is unique,” Barkawi said. “It’s more that Palestinians have created a library of motifs and designs that are connected to the land. It’s connected to their everyday life.”

It took Barkawi two years to stitch her thobe with five yards of fabric and over 70,000 stitches. She finished it in time to wear it to her Katib Kitab (religious ceremony).

“It was a really powerful moment because it was so special to wear something that I had spent so much time on, for such an important event,” Barkawi said. “At the same time, I got to celebrate a really nice milestone for me in life.”

Before 1948, village women used to design tatreez based on their personality, what they were witnessing and seeing around them, the type of land and animals that they were dealing with day to day and even the different relationships that they had.

“When I was doing my thobe my purpose and my intention really was to return to that practice of basically embedding,” Barkawi said. “I used my own experience and my own identity.”

Barkawi wants to bring the history and identity of tatreez to Palestinians all over the world, by teaching the parts of tatreez she wished she had access to, the history and the idea of designing it for yourself. By practicing and preserving the art form, it is in the long run working towards a liberated Palestine.

“My whole goal is to help anyone who is out there who has any ounce of Palestinian in them to feel like they are part of the Palestinian narrative, because they are,” Barkawi said. “Unfortunately, because of the occupation, this is just a natural byproduct of being a people that is dispersed and disconnected from their homeland. This is just part of the process.”

Every time Barkawi hosts an online workshop, she leaves energized and excited because of the energy feeding back into her.

“It’s witnessing that kind of experience, like that immediate connection, even if you’re not Palestinian,” Barkawi said. “People are able to connect to Palestine in this way,in the grand scheme of things, especially as Palestinians are fighting for liberation and justice. I think that’s really beautiful.”

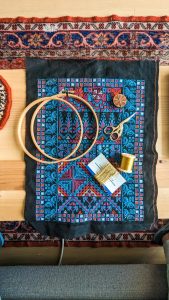

!["There's so much wisdom in our ancestors," Barkawi said. "There's a reason why they have this practice and it's been going on for centuries. It's because it helps you just take a moment and breathe and just focus on something [to] remove your worries." Photo provided by Lina Barkawi.](https://rhsrumbler.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/IMG_2523-1200x800.jpg)